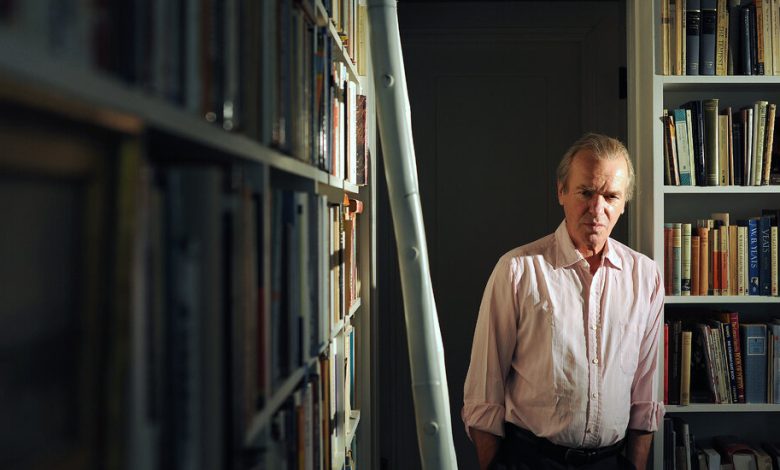

A Brief Guide to Martin Amis’s Books

Martin Amis, a giant of British fiction in the late 20th century, died on Friday at 73. As the former New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani wrote of Amis in her review of his 2000 memoir “Experience,” he was “a writer equipped with a daunting arsenal of literary gifts: a dazzling, chameleonesque command of language, a willingness to tackle large issues and larger social canvases and an unforgiving, heat-seeking eye for the unwholesome ferment of contemporary life.”

He was primarily known for unleashing that arsenal in scabrously witty and linguistically daring novels, but he was also an essayist, memoirist and critic of the first rank. The books below chart some of the peaks of Amis’s career.

‘The Rachel Papers’ (1973)

This was Amis’s semi-biographical first novel, and it introduced him as an omnivorous wit and dark observer of life. The book is about Charles Highway, a wise-up teenager, and his first love, Rachel Noyes, in the year before he leaves for college.

The novel is a “crotch-and-armpit saga of late adolescence,” our reviewer wrote, describing Charles, an aspiring writer, as “a compulsive pimple-squeezer, nostril tweezer, used handkerchief inspector and wrinkle enumerator. … It takes a certain comic talent to make Charles the delectably unappetizing creature he is, and Martin Amis has it.”

‘Money: A Suicide Note’ (1984)

Many readers consider this the best of Amis’s early novels. It tells the story of John Self, an British American director of television ads who comes to New York to shoot his first feature film. He’s a lout, he’s a slob, he’s a mess — and he is enormously fine company on the page.

“The book’s dash and heft and twang serve a deeper energy,” our reviewer, Veronica Geng, wrote. “A reimagined naïveté that urgently asks a basic, grand question: What on earth are the rest of us supposed to make of the spectacle of a fellow human getting totaled?” Amis himself appears in the novel as a character, “a high-minded ascetic type given to theoretical chitchat about the art of fiction and the phenomenon of ‘gratuitous crime.’”

‘